Triumph of the Domestic Workers

The installation work „Triumph of the domestic workers“ was part of the group exhibition "The Potosí Principle" at Reina Sofía/Madrid, Haus der Kulturen der Welt/Berlin and Museo Nacional/a Paz in 2010 and 2011. I realized this work together with Stephan Dillemuth and Territorio Domestico, a group of organized domestic workers in Madrid. In the exhibition you can see a painted canvas on bycicle wheels and with gearwheels on its front, a video of the performance we made in the streets of Madrid, as well as texts, fotos and stage props of this performance.

But first to the original painting: As you know, all the contributions of the exhibition “The Potosi Principle” refer to historical paintings. Ours is “The triumph of the name of Jesus”, painted by Juan Ramos from 1703. Until today, it is in the church of the village Jesus de Machaca, between La Paz and the Titicaca Lake in Bolivia. At the time the curators visited the place, there were stolen four small paintings from the church and the community refused the loan. In colonial times, Jesus de Machaca had strong connections to Potosí. The caciques traded in quicksilver, which was important for the explotation process of the silver. On the other hand, they liberated their people from the forced labour system in the mines, the mita. Instead of them, they contracted mingas, payed workers and kept their labour power in Jesus de Machaca. They also bought and handed the landed properties over to the communities. (Chariots motifs exported to Latin America - images were the most important medium of christianization during colonial times.)

This “Triumph of the name of Jesus” shows a chariot with several floors and the prophets, church fathers, apostles and saints of the catholic church on it. On the top of the chariot is the eucharistia. The four evangelists seem to pull the chariot – their sashes seem to disapear in the mouth of the serpent/Leviathan/Siren which squirms around the car. (We had different interpretations on this.) Above the chariot, we see Ignatius from Loyola, founder of the jesuitic orden (really important for the missionary work in Latin America), and behind him, with the bible in his hand, John Baptist. On the flag are sitting the allegories of church, faith and justice.

Behind the chariot, we see the familiy tree of Jesus: It begins with Abraham or Joshua with a schofar (the instrument which tumbled down the walls of Jericho), then there is King David or Salomon and finally Maria and on the top, the baby Jesus.

But under the wheels of the chariot, there are four women who represent the four continents. A much-discussed question when looking at the picture from JdM was: Who actually sets the wagon in motion? Is it the four evangelists in front of the wagon, the siren twining around it, or the four persons under the wagon moving its wheels with their hands?

I go on with the actual work and its context: First, this is domestic and care work:

In the rich countries, we are having a boom of domestic labour. More and more children, elderly persons and people with disabilities are being cared by domestic workers who often work under precarious conditions, that means for example without contract and without regular residence permission. A new type of female migration has come up out of these reasons in the last years. Female migrant workers not just only contribute to economic growth of their home countries by sending money, they also contribute to maintain economic standards in the countries they are working in. By leaving the care of their families in hands of other women (from the family or poorer persons) the migration of women leads to the creation of global care chains. As a disputed political field, care work gives birth to new gender subjectivities, hierachies, desires and resistances.

I met Rafaela from Territorio Domestico on a conference in 2008. Herself a domestic worker, she told about how the women of her group held out theirselves as lawyers in order to recover the wage of an undocumented colleague who was kicked out of her work without getting paid. They succeeded. The women, most of them latin americans, have founded the association Sedoac (Active Domestic work) in 2006. Territorio Doméstico is a constructive location in the self-organized feminist center Eskalera Karakola in Madrid where women, collectives and activists of various nationalities and with different experiences, who work as domestic workers or are otherwise connected to this issue, are meeting once a month. Together and along with other domestic workers’ associations and collectives, SEDOAC and Territorio Doméstico are fighting for equal rights of domestic labour, against precarization, and for the rights of domestic workers no matter what their residence permit status is. I began to work with the group in october of 2009, having meetings with the group and talks with different persons. This was actually the main base for the performative work we realized in february and march of 2010.

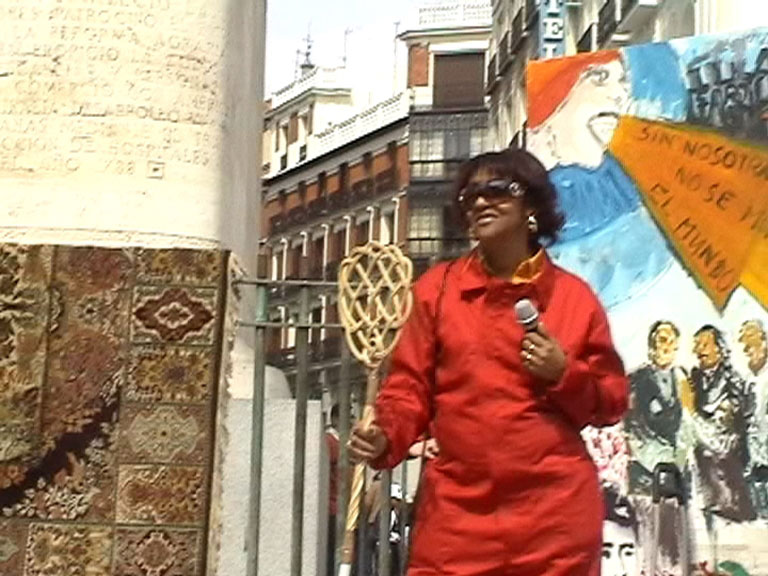

During this time, I worked with six domestic workers on four short documentary based scenes which thematize the conditions of a domestic worker's daily life: Migration, precarious work conditions, exploitation and irregular residence. The performance was part of the „International Action day of the domestic workers“ in the center of Madrid on 28th of march were hundreds of women took part.

The scenes had to be short and good to understand – even without hearing the words. The most adequate form for this we found was Agit Prop. The short scenes about repression and resistance in the daily life of the domestic workers were presented by themselves frontally and very agitative. At the time, the performance fitted in with the other parts of the demonstration. For example, the manifesto was read in front of the chariot/picture, the carpet and the statue in the middle of Plaza del Sol after our last scene there.

A very important part of the Performance was the painting on bicycle wheels and gearwheels moving with the movement of it, which acompanied the demonstration and was the scenery for the scenes. Territio Doméstico, Stephan Dillemuth and me painted it together on a sunday with grilled chicken and Coca Cola.

We talked together with the women about the painting of Jesus de Machaca and what could be the new interpretation we could give to it. This collage shows the step before the common painting: you see various revolutionary women / icons of the women's and workers' movement, the many-headed hydra instead of the leviathan. The hydra attacks the judges of the spanish higher court, the Audiencia Nacional, because they represent a fascist spain. At the time of the painting, they were covering the Gürtel case, a corruption case in which the spanish conservative party is deeply involved, and they fired the judge Garzón who was working on the implementation of the memory laws who concern the fascist past.

Care and Domestic work is in its different forms the base for social and capitalistic production. Reproduction work as central element of the society is dovetailed with all other areas of production, be it companies, universities, hospitals or careers in general. All depend in the end of the work of these women who mainly come from Spain's former colonies.

In order to visualise this principle and domestic work in the society, the group Territorio Domestico has developed its own symbol: a system of gearwheels set in motion by a female domestic worker. Obliged to the stock of images of the classical labor movement, domestic work now takes on the central position in regard to factory labor. These gearwheels who are very present in the painting, are the link between the colonial painting/situation and the actual system of colonialism, and it focusses on the power of the persons under the wheels – answering the question of “Who moves the wagon/world?”.

Presentation during the workshop on the opening of the exhibition “The Potosí Principle” at Haus der Kulturen der Welt, Berlin, 8th and 9th of October, 2010